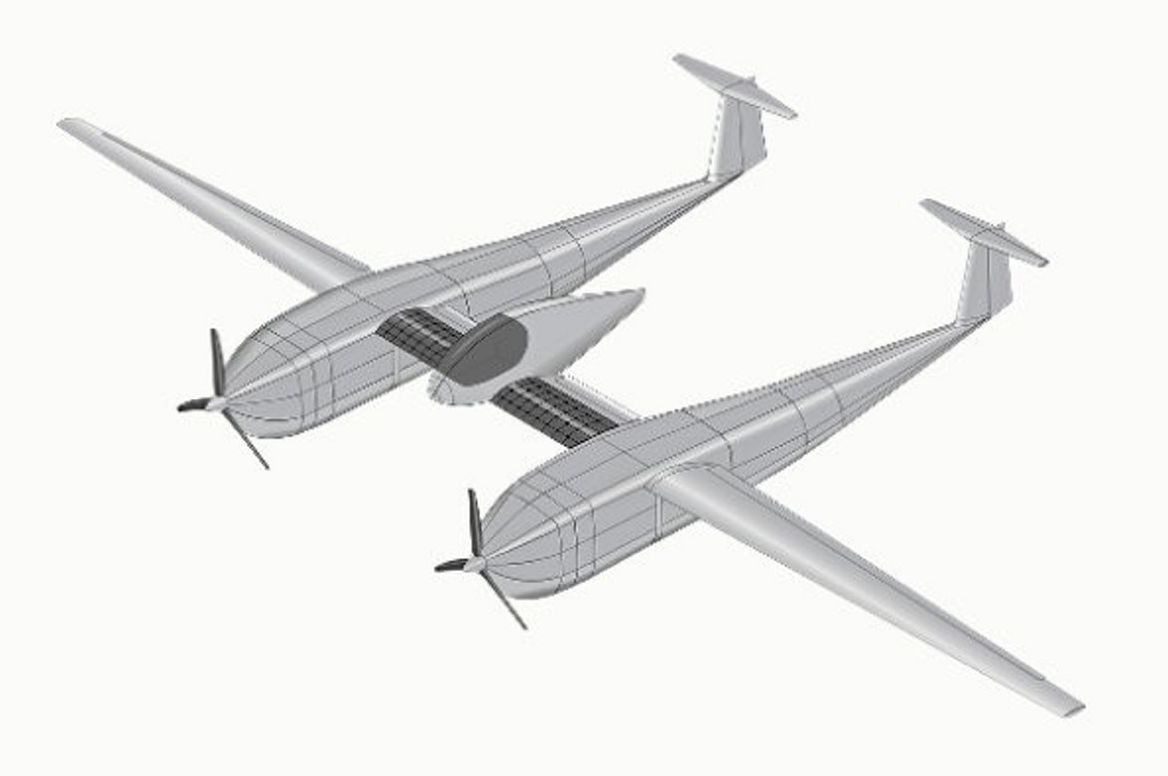

Swiss explorer unveils plan to fly non-stop around the world in a green-hydrogen-powered airplane

A Swiss explorer who comes from a long line of famous adventurers has announced plans to circumnavigate the world in an aircraft powered solely by green hydrogen.

Bertrand Piccard, 65, was the first person to fly non-stop around the world in a balloon (along with co-pilot Brian Jones), back in 1999, and also flew a solar-powered plane called Solar Impulse around the globe in 2015-16 (with co-pilot André Borschberg).

Now Piccard is building a hydrogen-powered plane called Climate Impulse, which he plans to fly non-stop around the equator in just nine days in 2028, accompanied by Italian co-pilot Raphaël Dinelli, a professional sailor whose life was famously saved in 1998 by British yachtsman Pete Goss while both were competing in the Vendee Globe solo round-the-world yacht race (which he later wrote a book about).

The new project is described as a “climate action adventure aiming to restore confidence in technological solutions for the common good” and “an environmental flagship aiming to play its part in revolutionizing the aviation sector and beyond”.

“Climate Impulse represents a technological breakthrough,” says the press release announcing the project.

“Beside the production of green hydrogen from renewable energies, and its use through fuel cells to feed electric motors, the major challenge lies in maintaining liquid hydrogen at -253°C during an estimated nine days of flight. This will require revolutionary innovations in the creation of adapted thermal tanks, opening new horizons in aviation technology. The collaboration with [science company] Syensqo will enable Climate Impulse to develop these cutting-edge systems.”

Article continues below the advert

Construction of the Climate Impulse — which will have two liquid-hydrogen tanks — will take two years, under the direction of Dinelli, who is also a pilot and “composite engineer”, even though a team supported by aircraft manufacturer Airbus and consultant Capgemini has already spent two years on research, development and design.

“Syensqo’s composite materials, films and additives will be crucial to the manufacturing of the entire structure of the hydrogen aircraft, its fuselage to the wings and hydrogen tanks. It will provide lightness, alongside mechanical and thermal properties,” the press release explains.

“When it comes to green hydrogen, the company’s high-performance materials (for Proton Exchange Membranes and binders for electrodes of the fuel cell) will be key enablers to confer exceptionally high-power density and efficiency, also allowing more compact design of the plane.”

The private project is being sponsored by French bank BNP Paribas, the charitable arms of Engie and Schneider Electric, oilfield services company SLB (formerly Schlumberger), Deutsche Telekom and others.

The record-breaking Piccard family — and Star Trek

Bertrand Piccard — who describes himself as a “serial explorer, psychiatrist and clean technology pioneer” — is the son of Jacques Piccard, who in 1960 became the first person to reach the floor of the Mariana Trench, the world’s deepest point (along with co-pilot Don Walsh).

And Bertrand is also the grandson of Auguste Piccard, who in 1931 became the first person to ever enter the stratosphere — in a hydrogen balloon with a spherical pressurised gondola (along with his assistant Charles Kipfer) that he designed himself.

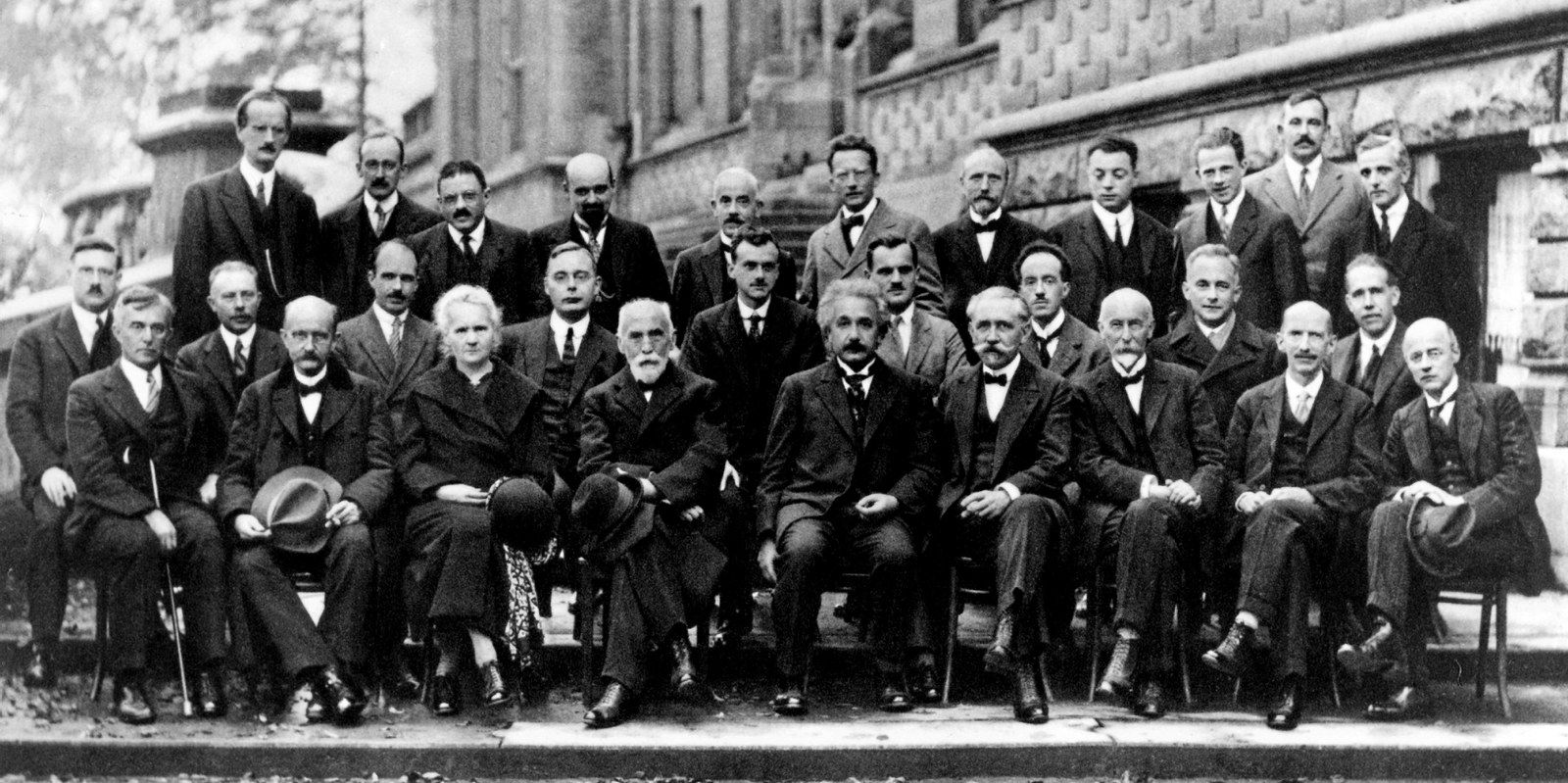

Auguste, a professor of physics, also discovered uranium-235 — the key ingredient in nuclear power plants and weapons — and knew fellow physicists Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr and Marie Curie.

Auguste also invented the submarine-like bathyscaphe that his son Jacques used to descend to the bottom of the Mariana.

Auguste’s twin brother Jean Felix Piccard — Bertrand’s great uncle — was also a professor, an inventor of high-altitude plastic balloons and an intrepid balloonist, making the world’s first “cluster balloon” flight in 1937. In order to descend, he was supposed to release some of the 98 gas-filled latex balloons, but some got stuck and he resorted to shooting them down with a pistol he had brought along for emergencies. This rare mode of multi-balloon transport was later co-opted in the Pixar animated movie Up.

Jean Felix’s American wife Jeannette often travelled with him on his adventures, becoming the first woman to enter the stratosphere — in a hydrogen balloon — in 1934. The launch of that journey — in the 15-storey-tall Century of Progress balloon was attended by 45,000 spectators at Henry Ford’s airport in Michigan.

On that flight, the Piccards (along with their pet turtle, Fleur de Lys) broke the world altitude record — before crash-landing into some elm trees, breaking several of Jean Felix’s bones.

In 1974, 11 years after her husband died, at the age of 79, Jeanette became the world’s first female ordained Episcopalian priest.

Jeanette and Jean Felix’s son Don (and his co-pilot Ed Yost) became the first people to cross the English Channel in a balloon, in 1963. Don later started his own balloon company and is credited with making hot air balloons safer through several innovations.

It is widely reported that the lead role in Star Trek: The Next Generation — Captain Jean-Luc Picard (played by Sir Patrick Stewart) — was named after either Jean Felix or Auguste or both by the show’s creator, Gene Roddenberry.

Indeed, Bertrand has stated on the record that Jean-Luc was named after Jean Felix.