The nuclear power station at the centre of the political divide in Scotland

Paris GourtsoyannisWestminster correspondent

BBC

BBCAlong a remote stretch of the north Somerset coast, views of rolling hills and farmhouses are suddenly interrupted by a thicket of construction cranes.

Here in south west England, along the Bristol Channel, is Europe’s biggest building site. Workers swarm over two enormous domed concrete structures, as the cranes dance overhead.

Up close, it feels like watching a pair of ancient pyramids being built.

When they are finished, the twin reactors of Hinkley Point C will form the first nuclear power plant built in the UK for 30 years.

The project is part of a global nuclear renaissance and, at a cost of nearly £48bn in today’s money, everywhere you look are signs of the huge investment being made by EDF – the French state-owned energy company behind Hinkley C.

The site feels like a small town, with dedicated fire and ambulance stations, and its own police officers.

Local butchers and farmers have been brought together to help feed the 15,000-strong workforce.

The on-site training centre resembles a sleek new college building. To get staff to work without clogging rural roads with traffic, EDF even operates its own fleet of nearly 200 buses – the largest in private hands in the UK.

EDF

EDFHinkley C is also at the centre of a major political divide in Scottish politics, which is set to emerge as one of the big arguments in this year’s Scottish Parliament elections.

That’s because a project like it would be impossible in Scotland – under the SNP, the Scottish government opposes any new nuclear development.

“Across the UK, there’s currently 98,000 people working in nuclear. We think there’s the potential for thousands of those jobs to be in Scotland,” says UK Energy Minister Michael Shanks, a Scottish Labour MP.

“Unfortunately at the moment under the SNP’s policy, we’re turning away that opportunity in Scotland, and we want to turn that around.”

But Shanks’ opposite number in the Scottish government says its opposition isn’t based on ideology, but practicality and public consent.

“We are concentrating on renewables, we are concentrating on green energy,” says Gillian Martin, Scotland’s energy secretary.

“We do not want new nuclear, and I do not believe the people of Scotland want new nuclear.”

Nicola Fauvel, the newly-appointed station director at Hinkley C, is only the second woman to run a nuclear power plant in the UK.

For her, the plant “represents the rebirth of the nuclear industry in the UK”.

Fauvel also happens to be one of the 1,200 Scots in the Hinkley C workforce.

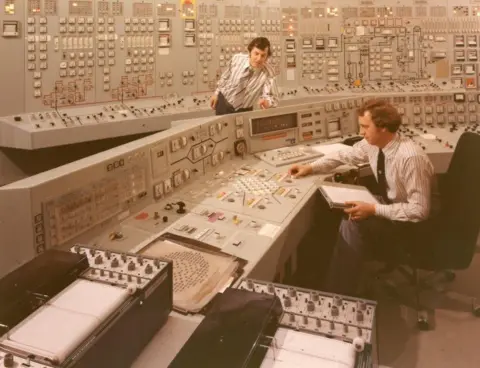

After studying mechanical engineering at Strathclyde University, her first graduate job was with EDF, at Torness nuclear power station in East Lothian.

She says being in charge of a nuclear power station still under construction is like getting under the bonnet of a new car before taking it out for its first drive – knowledge she has been building since the start of her 26-year career.

“Those 10 years at Torness were fundamental to me understanding the nuts and bolts of what a nuclear power station is,” she says.

“There’s been no new nuclear power stations built since then.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor Scottish graduates today, starting a career in the nuclear industry can mean a commute to match the scale of Hinkley C itself.

Fraser Gorvett grew up on the Scotland-England border, and joined the EDF graduate scheme after a degree in business management at Stirling University.

“I’m very passionate about sustainability,” he says. “My career goal during university was to find something that was making an impact, making a difference.”

His job as a commercial assistant involves managing contracts in the Hinkley C supply chain, and brings him to the site for one week a month.

On the way to and from Bristol Airport, Gorvett finds he has plenty of company. “A lot of the people on the bus are flying to Edinburgh and Glasgow,” he says.

Other young graduates have decided to make the move south permanent.

Phoebe Verstralen and Jack Lamb both studied physics at the University of Glasgow. Verstralen is a trainee reactor operator, and Lamb will work in radiological protection.

They are enjoying life in the southwest, and feel like they have entered the industry at the perfect time – but they also miss home.

“You’ve got to go where the jobs are, and unfortunately the jobs are in south west England,” Lamb says.

Most of their coursemates have had to make the same move.

“For graduate schemes, it was pretty limited in Scotland. I knew that I wanted to go into the nuclear industry,” Verstralen adds.

“I pretty much moved as far away as you can, from Aberdeen to Bristol. I would have loved the opportunity to stay in Scotland and be closer to my family.”

Others in the middle of their careers have also had to make the difficult decision to relocate.

Leigh Yule, a commissioning manager, spent over a decade working at Torness.

“For me to get longevity in my career, I was looking elsewhere. Hinkley C was one of the nearest options,” he says.

“The risk that you’re looking at is an intelligence drain from there, [people] that have spent years like myself working in the nuclear industry, that leave Scotland.”

David Upex relocated to Hinkley C after 13 years at Hunterston nuclear power station in Ayrshire.

Four of Upex’s colleagues initially planned to join him, but in the end only one did. Two others have now left the nuclear industry altogether.

“For myself it was quite easy to make the decision to come down here,” he says.

“It was a bit more challenging for my wife and my daughter. It was the first time they’d been away from home.

“If there was a Hunterston C under construction, would I be here? I don’t think so.”

Nuclear development stalled

Scotland has a long history with nuclear power.

The UK tested the technology at Dounreay, in the far north of the Highlands, and became a world leader, building the first ever nuclear power stations – with Chapel Cross in Dumfriesshire among the first wave – in 1959.

By its peak in 1997, nuclear power was responsible for more than a quarter of the UK’s electricity supply. But as safety concerns and the cost of building new reactors grew, nuclear development stalled around the world.

One by one, the UK’s ageing nuclear power stations were shut down, and nuclear power now contributes to less than 13% of the country’s electricity.

Hunterston stopped generating in 2023. Torness is Scotland’s last working nuclear power station, and is due to be decommissioned in the 2030s.

When it closes, three quarters of a century of nuclear history in Scotland will come to an end.

Meanwhile, the UK government is throwing its full backing behind the nuclear renaissance, a directive that industry insiders say comes straight from the prime minister’s office and Chancellor Rachel Reeves.

Out of an £8.3bn budget for Great British Energy, the UK government’s publicly-owned energy company, £2.5bn is earmarked to support nuclear development.

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer has promised a “wall of money” to invest in nuclear power if Labour wins May’s Scottish election.

But if nuclear investment did come to Scotland, it wouldn’t look like Hinkley C.

Privately, government and industry insiders admit that the age of large-scale nuclear power is probably over.

Instead, future nuclear development is expected to come in the shape of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), which produce less electricity but will be cheaper and quicker to build.

Wylfa on Anglesey, in North Wales, will host the first SMRs in the UK, and more sites will eventually be identified across England and Wales.

Rolls Royce has won the competition to design the UK’s first SMRs and is expected to sign a formal contract imminently. Its business model is based on a multi-billion pound investment in at least 10 reactors across the UK.

Nuclear sites need significant regulation, set out in law, both while power plants are operating and during decommissioning, which takes years.

That means the legal framework is in place for Hunterston and Torness to be prime candidates for SMRs – if the ban in Scotland is lifted.

Industry insiders say that within five years – the length of a Holyrood parliament – work could begin on new reactors in Scotland, generating investment and jobs.

That means having a political debate that provokes strong views on either side.

Supporters of nuclear power believe it has a crucial role to play, even as the world turns towards renewables to combat climate change.

It provides what’s known as “baseload power” – a constant, reliable source of electricity, free of carbon emissions, regardless of whether the wind blows or the sun shines.

Nuclear Decommissioning Authority

Nuclear Decommissioning AuthorityThe Scottish government says Scotland can meet all its electricity needs from renewables alone.

Critics say that when wind power isn’t generating, Scottish consumers end up paying for nuclear energy whether they like it or not, through electricity imports – while exporting the jobs and investment to England, or even abroad to France.

Shanks says: “This is a huge opportunity, it’s an economic opportunity, it’s an industrial opportunity, Scotland could be at the forefront of benefiting from it.

“And I genuinely think that on the ballot paper in May is that energy security question – you either have a credible plan for the long-term future of Scotland’s energy security, or you have the short-term ideological thinking from the SNP.”

But nuclear power isn’t cheap. Hinkley C is already billions of pounds over budget and at least four years late, making the UK the most expensive place in the world for new nuclear development.

Much of that extra cost and delay has been blamed on the Covid pandemic, but a major review last year also found that excessive environmental and safety regulations contributed to the overruns.

EDF and the UK government both say lessons have been learned at Hinkley that will help make construction of its sister station, at Sizewell in Suffolk, cheaper and smoother to build.

High costs

After a gap of 30 years, the hope is that the cost of nuclear technology will fall – as it has done for wind and solar power.

The contract signed with EDF for Hinkley C also gives a 35-year guarantee to pay £127 per megawatt hour for its electricity, a figure that rises with inflation.

Under a scheme known as “Contracts for Difference”, low-carbon electricity suppliers are compensated if their agreed “strike price” is above the wholesale cost of electricity on the open market.

That wholesale price has been between £80 and £85 since mid-2024.

That reflects the high cost of building Hinkley C, but supporters of nuclear power say that it is a guarantee against the volatile global market for fossil fuels.

If Hinkley C had been generating electricity when the cost of energy spiked after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, bill payers across the UK would have saved a combined £4bn.

Cost is one of the main arguments cited by Martin, when asked about the Scottish government’s case against new nuclear.

“It’s far too expensive… It is not an immediate solution to anything,” he says. “It is long term, it’s very expensive, and crucially, it is not going to bring down people’s energy bills.”

Hinkley Point C

Hinkley Point CNuclear energy has always been controversial.

The British nuclear industry is proud of its safety record, but opponents argue that while the technology might be clean and safe – it isn’t completely clean, or completely safe.

Historically, major disasters abroad have shaken public faith, even if the circumstances are specific to each incident.

The 2011 Fukushima disaster, triggered by a major earthquake and tsunami in Japan, pushed the German government to phase out nuclear power – a decision that some argue left Europe’s biggest economy overly-reliant on coal, the dirtiest form of energy.

Nuclear power also produces radioactive waste; disposing of it can be costly and comes with environmental risks.

The UK government is currently looking for a site to build an enormous underground storage facility for all its radioactive waste, some of which will have to remain buried for thousands of years before its safe.

Back at Hinkley, Fauvel looks out over the site as the sun casts lengthening shadows.

“I’m going to hopefully see this power station enter the generating phase by the end of this decade,” she says.

“It’s a dream, really, that we can bring a power station to life in Scotland, because I think it’s hugely beneficial economically, for skills – and because we’ve got such a strong engineering heritage.

“It would really do justice to that heritage to see something like this, come out of the ground in Scotland.”

Voters in May will decide whether that future is possible – or whether in Scotland, nuclear energy only has a past.