MENA nations ‘should export direct-reduced iron made with green hydrogen, rather than the H2 itself’: think tank

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is expected to be a hub for cheap green hydrogen production, with many developers indicating the vast majority of this H2 will be exported to demand centres in Europe and Asia.

But a new report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) suggests that rather than try and send green H2 outside their borders, MENA countries could be better served by using these molecules to displace fossil gas in existing direct-reduced iron (DRI) production.

DRI — where hydrogen or fossil gas is used to extract iron from ore, rather than coal-fired blast furnaces — is still extremely marginal, only representing 3-4% of the total global iron-ore trade.

However, of this, MENA represents 46% of DRI production worldwide, producing 58.48 million tonnes in 2022.

The combination of DRI with electric arc furnaces could enable near total elimination of CO2 emissions, if using renewable electricity.

While IEEFA acknowledges that this results in far fewer greenhouse gas emissions compared to traditional blast furnaces, plans to expand this capacity while continuing to use natural gas would “still add to MENA nation’s domestic carbon emissions at a time when pressure to increase emissions reduction ambition is increasing ever more”.

Article continues below the advert

The think tank also highlights that carbon capture and storage (CCS) is unlikely to be an effective solution for decarbonising these operations.

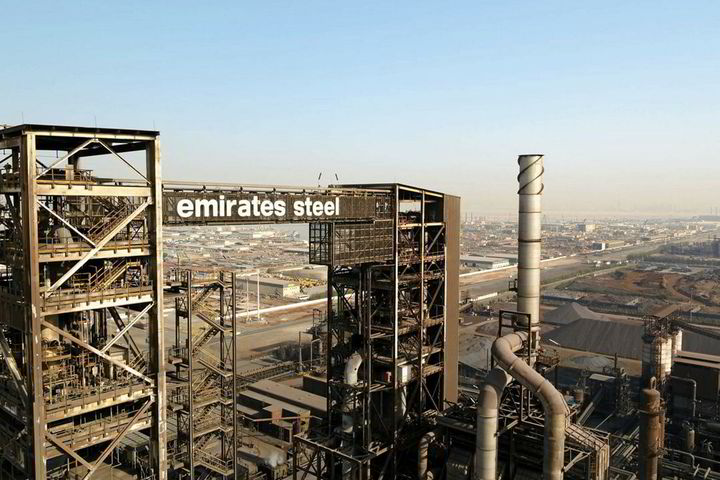

While MENA has seen the world’s first steel plant using CCS — Emirates Steel Arkan’s Al Reyadah project in Abu Dhabi has been operational since 2016 — it only had a 30% capture rate in 2022, while the CO2 has been used in enhanced oil recovery, increasing the production of fossil fuels.

“Demand for green steel is rising, led by car manufacturers, and it seems highly likely that steel customers will increasingly want accurate standards that define green steel and will not want fossil fuels to be part of their supply chains,” IEEFA warns.

Imports of steel products into Europe will also be regulated by the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which effectively taxes emissions at a similar rate to the price its internal steelmakers have to pay on the Emissions Trading Scheme.

This is expected to drive additional demand for green iron and steel as the cost of conventional steel increases relative to the green premium.

“The import of green HBI [hot briquetted iron, a form of DRI] is likely to be crucial to Europe’s efforts to decarbonise its steel sector, and MENA is ideally placed geographically to supply it,” says IEEFA.

Although European steelmakers have received hundreds of millions of euros in subsidies for DRI pilot projects, a full switch away from blast furnaces depends on a steady supply of cheap green hydrogen, much of which is expected to be imported.

However, “hydrogen shipping poses challenges such as low efficiency, high pressures, and the need for extreme temperatures during conversion and reconversion,” the report warns.

If transported as a liquid, hydrogen has to stay at temperatures below minus 253°C, compared with minus 162°C for LNG. Meanwhile, because hydrogen has a lower energy density than natural gas, “it also requires 2.5 deliveries to transport the same amount of energy as one cargo of LNG”.

This means that “while hydrogen liquefaction consumes 30%-40% of its energy content, LNG needs less than 10% — another argument for keeping hydrogen in gaseous form to avoid energy loss”, the report adds.

Meanwhile, hydrogen carriers such as ammonia require additional energy for conversion and reconversion.

IEEFA estimates that by 2030, transporting H2 via carriers would add $2.50-4.50 per kilo of hydrogen delivered. This means that if 51kg of H2 is needed in DRI with electric arc furnaces to produce one tonne of steel, the transportation cost of hydrogen alone could add $128-230 per tonne of crude steel.

While the paper does not provide a comparative cost estimate for importing green iron, it does say: “HBI production and transportation offer energy efficiency and eliminate energy losses that may occur when hydrogen and iron ore pellets are transported separately.”

And it also points out that eight million tonnes of fossil-gas-derived HBI was shipped overseas in 2021, along with a further 15 million tonnes transported by rail and inland vessels, demonstrating the relative ease at which it can be shipped, compared to liquid hydrogen or ammonia.

The think tank also cites comments from Dutch bank ING’s global steel lead Erik van Doezum at a conference last month, when he pointed to a growing consensus that green iron production will probably decouple from steelmaking and move abroad to where renewable electricity is cheapest.

“I expect significant iron production to move to places like Northern Europe, Southern Europe and the Middle East and North Africa regions,” Doezum said. “Steel companies in Europe, Korea and Japan will have to make difficult strategic choices about where to produce iron going forward.”

However, IEEFA warns that DRI-EAF steelmaking requires extremely high-quality iron ore, citing a forecast from Brazilian mining firm Vale that there could be a DRI-grade ore supply gap of around 70 million tonnes a year by 2030 — although it plans to fill much of that gap by expanding its operations.

Competition between countries for this ore, and the share of the potential trade in green iron, is heating up.

Although Australia primarily exports low-grade iron ore for blast furnaces, IEEFA highlights that Korean steel giant Posco is planning to invest in a project in Western Australia to produce hot-briquetted iron for export.

Meanwhile, Brazil — which supplies most of the world’s DRI-grade ore — has seen interest from traditional steelmakers such as Nippon Steel and start-up H2 Green Steel as a location for future green iron hubs.

However, IEEFA also notes that Brazil has an advantage over many countries in MENA owing to its hydropower-dominated grid.

“Although renewable energy capacity is expanding in the region, the dominance of fossil fuels in MENA power grids means that green hydrogen can only be produced via dedicated solar or wind installations, not off the grid as in other regions,” the report warns, noting that this will almost certainly increase capital costs.

When it comes to additional water needs for hydrogen-based DRI, IEEFA estimates that “the hydrogen value chain could potentially add one cubic metre to the water requirement for” each tonne of green steel — compared to the current average consumption by steel mills of four cubic metres of H2O per tonne of steel.

This could present an extra challenge for countries in MENA that already face high levels of water stress, although desalination of seawater is only expected to add around $0.10/kg of hydrogen.