Natural hydrogen could ‘fundamentally change how we use energy’, US government official tells Senate committee

The potential of natural hydrogen is so great that it could “fundamentally change how we use energy”, but it is too early to say if it can be commercially exploited, US government officials told a Senate committee hearing yesterday.

Expert witnesses explained to the Senate Committee on Energy & Natural Resources what is known and not yet known about the prospects for commercial exploitation of what was referred to as “geologic hydrogen”.

“The potential for geologic hydrogen represents a paradigm shift in the way we think about hydrogen as an energy source,” said Dr Evelyn Wang, director of the Department of Energy’s Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy (ARPA-E).

“This new source of hydrogen could lower energy costs and increase our nation’s energy security and supply chain. In other words, it could fundamentally change how we use energy.”

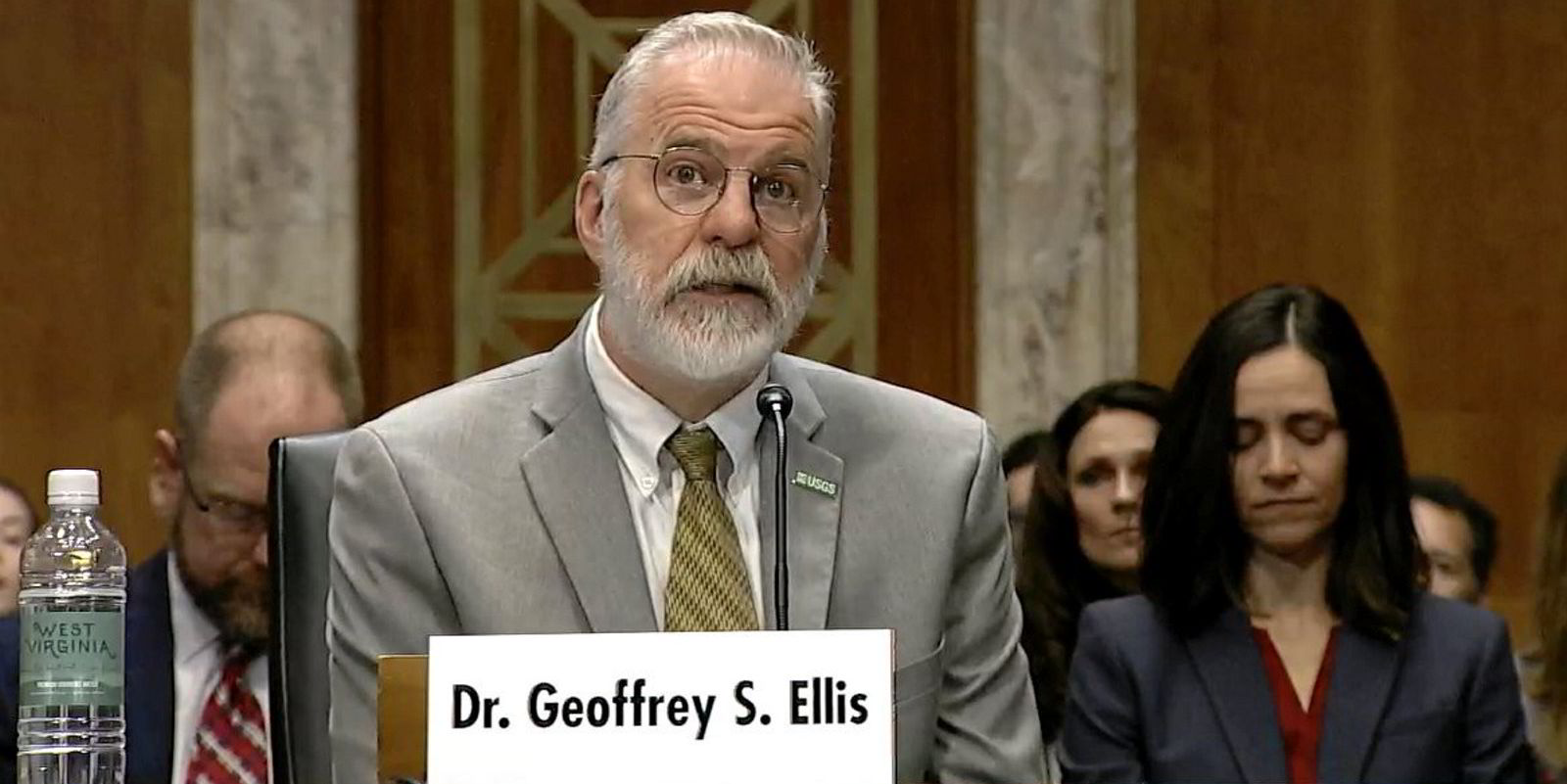

Dr Geoffrey S Ellis, who heads the geological hydrogen programme at the Department of the Interior’s US Geological Survey (USGS), added that estimates of “global geologic hydrogen resources range from thousands to billions of metric tonnes”.

“Based on historical data on other geologic energy resources, the vast majority of the in-place hydrogen resource is likely to be in accumulations that are too deep, too far offshore, or too small to be economically recovered.

Article continues below the advert

“However, the remainder could constitute a significant resource.”

The ranking Republican senator on the committee, John Barroso, addressed the third expert witness, Peter Johnson, CEO of natural-hydrogen company Koloma, quoting a comment attributed to the start-up’s key angel investor, billionaire Bill Gates, who apparently said: “It could be gigantic or it could be a bust, but if it’s really there, wow!”

Barroso asked Johnson: “So would you tell us why you think geologic hydrogen has real promise and won’t be a bust.”

Johnson replied: “I think the science of geologic hydrogen formation in the subsurface is very clear. There are hydrogen seeps all over the planet that have been documented. The question that needs to be answered is… are there accumulations that are large enough to be commercial? If you’ve got a really small puff of hydrogen from one well out on a farmer’s field, that’s hard to commercialise.

“The bust scenario is not that there’s no hydrogen under the ground, that science is established. The bust scenario is there’s nothing big enough or the only thing that’s big is in the middle of Greenland.”

He later said: “It’s a matter of finding large enough resources of high enough purity close enough to markets.”

Ellis told the committee that the USGS was in the process of “developing a conceptual geologic model for evaluating the potential for hydrogen accumulation in the subsurface… [that would map] the likelihood of finding geologic hydrogen resources in the lower 48 states of the US”.

Committee chairman Senator Joe Manchin, the controversial Democrat from West Virginia, asked Ellis when the USGS would be able to identify where the geological hydrogen was “because we’re not going to go out drilling until you tell us where to go”.

Ellis replied that the USGS is aiming to get “our initial map of prospectivity for the US by the end of this year”.

“But the second key point here is that once we have this map, it’s not going to tell you where to drill your wells. This is going to tell us where the best place is to start doing more detailed exploration.”

He added that according to the agency’s “initial efforts”, the most likely areas to exploit natural hydrogen in the US were along the East Coast, “all the way from New Jersey down to Georgia”.

“This is related to offshore iron-rich rocks that could be a source for hydrogen, and then it would be migrating towards the coastline.

“Another prospective area is the mid-continent rift where we have ultramafic rocks, these iron-rich rocks that extend all the way from northeast Kansas up through Nebraska, Iowa and into Minnesota, and up into Ontario and then down into Michigan.

“This is based on our understanding of where the source rocks are most likely to be, but it’s complicated.”

A short history of natural hydrogen development

In his opening statement to the committee, Ellis explained why no-one had thought to drill for natural hydrogen until only a few years ago.

“The existence of naturally occurring hydrogen is well documented in many geologic environments. Nevertheless, out of the millions of oil and gas wells that have been drilled to date, only a few dozen oilfields have been documented to contain more than trace levels of hydrogen.

“This has led many geoscientists to conclude that economic accumulations of hydrogen in the subsurface are non-existent. However, recent evidence indicates that we have simply not looked for geologic hydrogen resources in the right places with the right tools.”

He explained that a shallow water well drilled in the west African country of Mali in 1987 produced “an unexpected gas explosion and was quickly abandoned”.

“Nearly 25 years later, an oil and gas company returned to the site and discovered that the gas was more than 97% hydrogen. Subsequent exploration identified five geologic reservoirs containing nearly pure hydrogen gas. This hydrogen has been in production for more than 10 years and is used to provide electricity to a local village.

“This discovery was first described in the scientific literature in 2018 and stimulated new interest in the resource potential of naturally occurring or ‘geologic’ hydrogen.”

He added: “The geologic setting of the hydrogen accumulation in Mali is not unique, which suggests that geologic-hydrogen accumulations could be widespread. In fact, researchers have begun reviewing historical industry records and unpublished data and have uncovered historical discoveries of natural hydrogen that had gone unnoticed in numerous places around the world.”